“Voulez-vous la voir?”

“Voulez-vous la voir?”

par Robert Stein, November/December 2005

article publié sur americanheritage.com

Un jeune et ambitieux éditeur de magazine et un photographe tourmenté ont découvert ensemble une Marilyn Monroe que personne ne connaissait.

Un après-midi de 1955, je regardais à travers un verre de scotch à l'Hôtel Gladstone à Manhattan. J'en avais avalé plusieurs, mais ils n'ont pas réussi à dompter ma panique. J'ai été coincé vers le haut, et mon seul espoir, assis à la table et souriant sereinement, était mon ami Sam Shaw.

En tant que jeune rédacteur au magazine Redbook où j'avais été salué et encouragé, ce qui m'amena à aller très loin, si loin que mon travail était maintenant suspendu par le plus mince raccord - de la connexion de Sam à Marilyn Monroe.

Après avoir quitté Hollywood pour étudier à l'Actors Studio, Marilyn se retira de la lumière. Pour la première fois de sa vie sous les flashs, elle avait esquivé les photographes et les journalistes.

Après une vingtaine de films, un mariage titré et un divorce titré, elle était à New York pour se préparer à jouer dans des pièces comme Grouchegnka dans Les Frères Karamazov. Les articles de presse creusaient tous les clichés sur les comédiens qui veulent jouer Hamlet, en soulignant leur ridicule avec des photos de Sept ans de réflexion, Marilyn sur la grille de métro, un courant d'air ascendant soulevant sa robe blanche sur ses hanches. Elle a évité la presse presque entièrement, ce qui la rendait encore plus désirable. La difficulté d'avoir Marilyn était nouveau.

Ma crise a commencé quand j'ai fait quelque chose sur le personnage. J'ai vu une impression mal éclairée d'elle dans une classe de l'Actors Studio, couverte d'un manteau en poil de chameau et sans maquillage. Une ligne me traversa la tête: la Marilyn Monroe que vous n'avez jamais vu, et sans aucune hésitation, j'ai persuadé mon patron pour le graver sur la couverture de l'édition du mois de Juillet, qui partait sous presse 10 jours avant le reste du magazine. Je sautais d'un avion sans savoir si le parachute s'ouvrait.

Comme je m'étais jeté à l'eau, je savais qui serait avec moi - mon meilleur ami, le photographe Ed Feingersh, qui savait tout sur le parachutisme. Certaines de ses audaces doivent avoir déteintes sur moi, et nous nous sommes assis dans le salon du restaurant Costello pour planifier notre assaut sur la forteresse Marilyn.

Trois jours plus tard, nous n'avions rien. Il m'est apparu que, alors qu'il était un casse-cou, Eddie n'avait pas de cadeau comme un harceleur. Le premier après-midi, il a attendu pendant des heures dans le hall de l'hôtel de Marilyn, a pris une minute pour faire un appel téléphonique, et s'est retourné pour trouver des enfants brandissant un petit appareil Kodak Brownies, qui était la caméra omniprésente peu coûteuse de la journée: "Elle a posé pour nous! "

Avec des pages blanches se profilant pour l'édition du mois de juillet, j'ai appelé Sam, un photographe qui voulait être un producteur de film et avait travaillé dur ses amitiés avec la génération montante d'Hollywood, dont Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando et Marilyn. Sam et moi avions une fois partagé un bureau, et il a accepté de m'aider.

A l'hôtel Gladstone, Sam avait appelé Marilyn chez elle au téléphone. Comme d'habitude, elle était en retard. Nous biberonions nos boissons, lorsqu'un homme, grand et bronzé, regarda dans la salle et se dirigea vers la table.

«Sam, comment allez-vous?", avait déclaré Joe DiMaggio, en s'asseyant. "Marilyn m'a dit que vous étiez ici."

Quelques mois plus tôt, en évitant les journalistes comme à son habitude, DiMaggio avait été vu quittant le tribunal de divorce dans la douleur et la colère évidente. Maintenant, il était là, revenant fraîchement de la chambre de son ex-épouse, parlant d'elle, presque en babillant, avec un sourire d'écolier sur son visage, disant à Sam combien il était heureux qu'elle était loin de "cette foule du cinéma". En outre, le notoirement jaloux DiMaggio se pressait de revoir davantage Marilyn. "Elle veut encore que vous l'emmenez chiner", at-il dit en se levant avant de partir. Il m'a donné un rapide regard et sourit.

Quelques minutes plus tard, Sam me passa le téléphone de sa maison, et dans cette voix familière soufflée, Marilyn a accepté de faire une histoire en photos, suggèrant que nous nous rencontrions pour boire un verre l'après-midi suivant.

«Pourquoi», Marilyn demanda peu de temps après que nous nous asseyions, "ont-ils imprimé des choses sur moi qui ne sont pas vrai?"

Ce n'était pas une question rhétorique ni une plainte. Nous étions dans un bar à cocktails, et elle me regardait par-dessus son Scotch Mist avec une expression perplexe, attendant une réponse. De près, son visage était pâle et fragile, avec aucune lueur Technicolor, et ses yeux n'avait rien de la confiance qui émanait de l'écran.

Quelques minutes plus tard, il était clair qu'elle n'avait pas de conversation, pas de défenses sociales. Sam m'avait dit, si tu lui demandes: «Comment allez-vous?", elle va cesser de penser au lieu de répondre automatiquement "Bien." Et quand elle posait une question, elle attendait une réponse.

"Pourquoi font-ils ces choses?", elle persistait.

Je me suis lancé. "Parce que des photos de vous font vendre des journaux et des magazines, et quand il n'y a aucune excuse pour les faire fonctionner, ils vont imprimer des rumeurs et des ragots, tout ce qu'ils peuvent avoir". Quelque chose m'a poussé à aller plus loin: "Ils ne veulent pas vous blesser, juste vous utiliser."

Elle me regarda avec un demi sourire qui en disait long sur ce qu'elle savait au sujet d'être utilisée. Il a déclenché un flash-back dans mon esprit: Mike Cowles, l'éditeur de Look, m'avait raconté une de ses visites à la Twentieth Century-Fox dans les années 1940, quand un chef de studio lui fit la remarque: "Nous avons une nouvelle fille sur le marché avec quelque chose d'inhabituel. Au lieu de sortir tout droit, ses seins sont inclinés vers le haut. "Il l'a envoyé vers Marilyn, qui est venue en souriant, et il souleva son chandail pour montrer ce qu'il voulait dire. Elle n'avait jamais cessé de sourire.

Nous avons parlé de Sam pendant un certain temps, puis Marilyn a dit: «Il y a une autre raison pour laquelle je fais cela:. votre magazine ne s'est jamais moqué de moi» Ses yeux brillaient. «Ils m'ont même donné un prix."

Je me suis senti accepté et, en même temps, accablé par sa confiance. La femme la plus sexuellement célèbre dans le monde était comme un être enfantin et vulnérable, mais aussi utilisait son ouverture d'esprit pour obtenir ce qu'elle voulait pour quelques jours: ma loyauté. Toute sa vie, ce mélange d'innocence et de ruse avaient apparemment tiré des protecteurs et des traîtres, beaucoup d'entre eux étant les mêmes personnes.

Il ne fallut pas longtemps avant que quelqu'un ne surgisse. Le lendemain, j'ai reçu un appel de Milton Greene, un photographe médiocre et de classe mondiale débrouillard, qui l'avait convaincue de former un partenariat avec lui qui s'appelait les 'Marilyn Monroe Productions'. Nous pouvions faire l'histoire, dit-il, mais seulement avec un photographe à son service. Je lui ai dit de se perdre, et quand Eddie et moi avons rencontré Marilyn, le lendemain, je racontai la tentative de chantage. Elle fronça les sourcils, et nous avons commencé notre histoire. (Il lui a fallu un certain temps pour obtenir une image complète, mais finalement elle a viré Greene pour mauvaise gestion.)

J'ai dit à Marilyn que nous voulions la montrer telle qu'elle était vraiment: pas de pose, pas de baisers soufflés à la caméra, pas de configurations de studio, juste un regard droit dans sa vie.

À l'apogée des appareils à 35mm et de la lumière naturelle, Eddie adorait Henri Cartier-Bresson, dont les images ont été montrées non seulement dans les magazines, mais aussi dans les musées. Son idole ne permettrait pas d'imprimés à recadrer et à découper, et ce n'est pas non plus ce que voulait Eddie. Le «moment décisif» a été formulée dans l'œil du photographe, et le fait de modifier plus tard l'image serait comme de donner des coups tranchants dans un Renoir ou un Van Gogh. À une époque où les films italiens et français étaient montrés comme le duvet d'Hollywood, Eddie et d'autres ont transformé les photos des magazines en papier glacé, avec un réalisme à la volée. Le monde devenait granuleux.

Seul parmi les autres, Eddie voulait aller au-delà du simple témoin d'un événement avec son appareil, de le saisir et de montrer comment il avait l'air de l'intérieur - se risquant lui-même pour des moments que personne n'avait jamais vu. Il a pris des photos lors de l'exploration des patrouilles en Corée, attaché au périscope d'un sous-marin en plongé, sauté d'un avion avec des parachutistes. De retour à la maison, sur une piste de course avec des pilotes irlandais de Horan’s Lucky Hell, les coudes longés sur son corps, entre un angle de 45 degrés alors que les voitures étaient carénées par l'excès de vitesse, se trouvant si proche qu'il pouvait voir les marques de plis sur les pneus.

Petit, mince et voûté, avec un visage loin d'être beau, Eddie était magnétique pour tous ceux qui le connaissaient. Il était aussi un passionné de l'amitié comme de son travail. Il était un artiste pour les deux.

Il a vécu dans le présent, laissant les instants l'emmèner peu importe où ils le feraient. Costello était plus une maison qu'un lieu de rencontre. Il a dû avoir un appartement ou une chambre quelque part, mais durant toutes ces années où nous étions des amis proches, je ne les ai jamais vu. Il recevait son courrier et ses messages téléphoniques au Costello et passait toutes ses soirées au bar en ville, comme les gens qu'il connaissait allaient et venaient, se déplaçant à quelques mètres d'une table pour manger et, plus tard, si l'humeur était bonne, glissait des pièces dans le téléphone payant pour demander à une jeune femme d'appeler ses amis pendant que quelques-uns d'entre nous apportions une bouteille à boire et flirtions jusque loin dans la nuit. Son énergie était sans fin. Il passait des heures à parler avec enthousiasme, faisant des gestes, griffonnant sa version des chiens Thurber sur des serviettes, se levant en tournant pour garder le rythme, tapi comme Groucho dans un serpentin de glisse. La vie avec lui n'était jamais à l'arrêt.

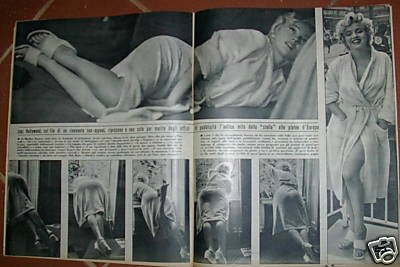

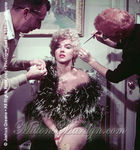

Suivant Marilyn, l'appareil photo d'Eddie en disait plus que ce que nous savions à l'époque. La Marilyn publique prenait des rendez-vous --essayant un costume pour faire des raccords pour monter sur un éléphant rose à une première charité du cirque, des rencontres avec les avocats et les agents (Twentieth Century-Fox l'avait suspendue pour décamper), une entrée remarquée en fourrure blanche à la soirée d'ouverture de la pièce de Tennessee Williams 'Une chatte sur un toit brûlant'. Avant de sortir, elle fit une performance photographique avec le bouchon d'une bouteille de Chanel n ° 5, caressant sa peau dans la volupté.

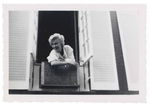

Mais entre les moments où elle était vue, il y avait une autre Marilyn, soudain vidée de son énergie, comme l'air laissé dans un ballon ouvert. Elle était assise dans une sombre chambre d'hôtel avec un verre à la main, et sortit sur la terrasse à ne rien regarder , que l'horizon de Manhattan. L'obturation d'Eddie restait maintenu en cliquant, et des rouleaux de films 35 mm remplis d'images d'une Marilyn Monroe que vous n'avez jamais vu: retirée et solitaire. Il ne lui a jamais demandé de poser. Elle savait qu'il était là.

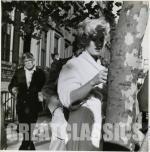

Marilyn n'avait jamais été dans une station de métro. Enveloppée dans son manteau de poils de chameau, ses fameuses mèches de cheveux maîtrisées, elle se dirigea vers la station Grand Central de l'IRT et descendit à la plate-forme. Personne ne l'a reconnu. L'appareil photo d'Eddie était gardé sur le clic tandis qu'elle se tenait dans la rame en direction de Uptown. Aucune tête ne se tourna.

De retour dans la rue, Marilyn regarda autour d'elle avec un sourire taquin. "Voulez-vous la voir?" demanda-t-elle; là, elle enleva son manteau, ébouriffa ses cheveux, et cambra son dos pour prendre la pose. En un instant, elle a été engloutie, et cela amena plusieurs bousculades, des minutes effrayantes jusqu'à se dégager de la foule grandissante.

Les deux Marilyns gardées en fondu. A l'essayage du costume, elle arriva comme une star, commandant un essaim de tailleurs, de couturières et de parasites, jusqu'à ce que l'Autre a brusquement émergée et fondit en larmes de frustration sur certains détails du vêtement. L'appareil photo d'Eddie capta tout, montrant la tension qui monte contre une jangle visuelle des cintres en arrière-plan. Il a formulé la scène dans la salle-aux-miroirs fragmentée et iréelle qu'Orson Welles avait créé autour de Rita Hayworth pour la finale de 'La dame de Shanghai'.

Tard, un après-midi, Marilyn a demandé ce que nous ferions à la fin de la journée, et nous l'avons emmenée à Costello. Là, John McNulty écrivait sur le lieu dans 'The New Yorker' depuis des années, mais le propriétaire, Tim Costello, avait réussi à l'empêcher de changer. Un regard sévère au-dessus de sa tasse de thé à la table du fond était plus efficace que le comité des règles d'un club privé. Le restaurant Costello n'a jamais été à la mode dans la façon dont un chauffeur de taxi a dit d'une autre salle, "Personne ne va plus là. Il y a trop de monde. "

Derrière le bar tout en longueur, était un bâton de marche prunellier, qui avait été cassé sur la tête de John O'Hara par Ernest Hemingway, personne ne se souvenait pourquoi. Sur le mur d'en face, étaient accrochés d'énormes dessins sur panneaux de fibres de James Thurber, si prisés par Tim qu'il avait eu les plus encrés, vernis, et, quand il a été contraint de déplacer son établissement juste à côté, il les avait soigneusement enlevés et remontés. Les panneaux étaient bruns avec l'âge et la fumée de tabac.

Thurber avait rempli les murs avec des images de chiens lâches (un chien en chasse par les lapins) et des petits hommes menacés par des femmes énormes ("Je te quitte, Myra, vous pourriez aussi bien vous habituer à l'idée», dit l'un dans l'embrayage d'une Amazone, qui faisait plusieurs fois sa taille). Une telle autodérision masculine convenait au lieu. Tim ne respectait pas les ivrognes bruyants et pugnaces.

Marilyn portait une blouse sans manches noire et un pantalon rayé. Elle s'assit à côté des dessins Thurber à une table en face du bar.

Tim, le plus souvent méfiant envers les étrangers, a été clairement intrigué par la flambée des cheveux blonds à notre table et, dans un geste rare, est venu prendre lui-même les commandes.

"Un tournevis s'il vous plaît," dit Marilyn. Tim était sans expression.

"Vodka et jus d'orange», a-t-elle ajouté.

Tim continuait à la regarder. "Nous ne servons pas de petit déjeuner ici", a-t-il dit.

«OK», dit agréablement Marilyn, "vodka 'on the rocks'."

Tim a donné l'ordre à son frère Joe au bar et retourna à la lecture de son journal. Plus tard, comme Eddie se dirigeait vers les toilettes des hommes, Tim l'a arrêté. «Qui est-elle?"

Eddie sourit. «Marilyn Monroe».

Le visage de Tim s'assombrit. "Je pose une question civile et vous faîtes de l'intelligence."

Eddie sourit à nouveau et Tim retourna à son papier.

Dans l'heure, plus personne d'autre ne donna à Marilyn plus qu'un coup d'oeil. Alors qu'elle partait, un photographe au bar tapota Eddie sur le bras. «Si vous revenez plus tard," at-il murmuré, «amenez votre petite amie."

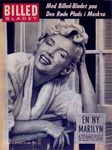

Les photos dans Redbook, avec mon texte et les légendes, ont montré une Marilyn inconnue et vulnérable, dans des tons doux de gris et noir. Le titre d'ouverture contrastait de sa tristesse solitaire avec un long shooting de 200 photographes près de l'éléphant piétinant, qu'elle avait montée au cirque.

Durant leurs jours ensemble, en dépit de la disparité dans les regards, je pouvais voir qu'Eddie et Marilyn étaient très semblables. Ils ont tous deux été en quelque sorte plus directement lié à la vie que le reste d'entre nous, et les plus vulnérables. Comme Marilyn, Eddie a été accordé à l'auto-parodie pour masquer la douleur d'être sans défense face à la vie quotidienne et, comme elle, désespéré de faire pleinement usage des dons d'une telle nature ouverte offerte.

Tout comme Marilyn craignait de sembler moins que parfaite devant les caméras et était toujours en retard, Eddie était obsédé par ce qu'il faisait derrière la caméra et ne laissait personne d'autre développer ou imprimer ses photos.

Chacun tenait à un idéal de l'Art comme si elle était la vie elle-même, et, comme il s'est avéré pour chacun d'eux, il l'était. Les films de Marilyn et les photos d'elle par Eddie, faisaient, à ceux qui les ont vus, se sentir plus vivant, mais en même temps, la peur pour leur sécurité, détectant le prix qui devrait être payé pour leur lumineuse ouverture.

Avant la fin de l'année, l'entrée de Costello sur Third Avenue a été démolie, en supprimant les piliers des habitués que Tim utiliseraient pour les stabiliser eux-mêmes tout en saluant les cabines dans les heures matinales.

Le séjour de Marilyn à New York la mena à son mariage avec Arthur Miller et elle tenta de devenir une épouse et une mère conventionnelle dans le Connecticut tout en faisant quelques films qui montraient sa capacité d'agir, ainsi que l'amplitude de la chair et de l'esprit.

Eddie s'est aussi marrié, et puis il tomba dans la crise de sa vie.

The Cliff était un bar sur la vingt-troisième rue. Eddie a utilisé son dernier centime pour un appel téléphonique, et je suis descendu pour l'empêcher de faire le saut périlleux.

Il avait commencé à aller mal quelques années après l'histoire de Marilyn. Après mon mariage, nous nous sommes moins vus, et ce fut une surprise quand il m'a dit qu'il allait se marier. Elle était d'une beauté blanche avec des pommettes hautes et un air imperméable qui flottait dans nos moments ensemble, dans un détachement qui, apparemment, sous l'impulsion d'Eddie à verser toute l'énergie qu'il permet de mettre en oeuvre pour trouver l'image parfaite dans la résolution de son mystère.

A leur mariage, j'étais derrière la caméra, regardant des images incongrues d'un livre d'images d'une mariée en blanc aux côtés d'Eddie en costume sombre et au sourire penaud, une partie de lui voyant tout cela d'une perplexité impuissante. Le mariage n'a duré que quelques mois, pendant lesquels il avait travaillé progressivement de moins en moins, pour finalement complètement arrêter, avant que son épouse a flotta hors de sa vie, ne laissant derrière elle que son regard énigmatique.

Après avoir appelé ce soir-là, nous nous sommes assis pendant des heures, essayant de comprendre ce qu'il pouvait faire, maintenant qu'il était trop paralysé pour faire la seule chose dans la vie qu'il était censé faire. Enfin, j'ai proposé une réponse: «Viens travailler pour moi. J'ai besoin d'un éditeur d'images."

J'étais le rédacteur en chef de Redbook en ce temps là, et l'idée faisait sens. Si Eddie ne pouvait plus prendre de photos, il pouvait les imaginer, proposer des sujets à des photographes, et les aider à faire du bon travail jusqu'à ce qu'il puisse commencer à faire à nouveau le sien.

Pendant quelques mois, ça s'est bien passé. De temps en temps, quand il était enthousiasmé par un travail, je disais sans le regarder: «Bien sûr, tu serais parfait pour ça» ou: «C'est ton genre d'histoire.» Chaque fois, il aurait gelé un moment, avant que ses yeux ne se vident et il secouait la tête.

Il a baissé sa consommation d'alcool, mais la dépression a empiré. Progressivement, il venait de moins en moins au bureau puis, finalement, plus du tout. Puis vint un appel téléphonique d'une femme qui avait eu une relation amoureuse avec lui pendant des années. Il était arrivé à sa porte la veille au soir et il était mort dans son sommeil pendant la nuit.

Pendant des années, j'avais demandé à Eddie d'essayer d'aller voir un psychiatre, mais ma demande ne pouvait pas casser sa certitude que la souffrance était inséparable de son don, qu'il ne pouvait pas échapper à l'un sans perdre l'autre. Dans le monde d'aujourd'hui, il -et aussi Marilyn, pour cette question- aurait peut-être été entretenu par des médicaments, mais à l'époque, il n'y avait pas de telle bouée de sauvetage.

Depuis, ceux qui ont aimé le travail d'Eddie ont essayé d'obtenir des musées pour lui donner la reconnaissance qu'il mérite. Mais il n'a pas été plus facile de l'aider dans la mort que pendant sa vie. Presque tous ses tirages et négatifs, si étroitement tenus, ont été dispersés et ont disparu, des photos magnifiques perdues à jamais.

Pourtant, quelque chose de lui demeure en vie, lié à jamais avec cette autre âme perdue. Sur les sites web, dans de nombreuses langues, les gens vendent des tirages de quelques-unes des photographies qu'Eddie prit de Marilyn de cette semaine en 1955. Les négatifs ont été trouvés dans un entrepôt, trois décennies après sa mort.

Marilyn a inspiré les fantasmes rescapés des légions d'écrivains, parmi lesquels Norman Mailer et Gloria Steinem. Vers la fin de sa vie, Arthur Miller se retourna sur son passé et se vit lui-même de cette façon. «J'ai passé cinq ans à essayer de l'empêcher de tomber de la falaise" , a-t-il déclaré à un journaliste en 2004, tout en justifiant 'Après la chute', la sale pièce d'auto-apitoiement qu'il écrivit peu de temps après sa mort.

Comme Eddie soit-disant sauveur, je suis resté avec non pas une apaisante consolation, mais seulement un sentiment permanent de perte.

“Do You Want To See Her?”

by Robert Stein, November/December 2005

article published on americanheritage.com

An ambitious young magazine editor and a tormented photographer together discovered a Marilyn Monroe nobody knew.

One afternoon in 1955 I was staring into a glass of scotch at the Gladstone Hotel in Manhattan. I had downed several, but they failed to subdue my panic. I was jammed up, and my only hope, sitting across the table and smiling serenely, was my friend Sam Shaw.

As a young editor at Redbook I had been praised and promoted, which led me to overreach so far that my job was now hanging by the thinnest thread—Sam’s connection to Marilyn Monroe.

After leaving Hollywood to study at the Actors Studio, Marilyn retreated from the spotlight. For the first time in her flashbulb life she was dodging photographers and reporters.

After two dozen movies, a headline marriage, and a headline divorce, she was in New York to prepare for parts like Grushenka in The Brothers Karamazov . The papers dug out all the clichés about comedians who want to play Hamlet, underlining their ridicule with photos from The Seven Year Itch , Marilyn on the subway grate, an updraft billowing the white dress over her hips. She avoided the press almost entirely, and that made her even more desirable. A hard-to-get Marilyn was news.

My crisis began when I did something way out of character. I saw an ill-lit print of her in an Actors Studio class, covered by a camel’s hair coat and no makeup. A line flashed through my head: the marilyn monroe you’ve never seen, and with no hesitation I persuaded my boss to engrave it on the July cover, which went to press 10 days before the rest of the magazine. I was jumping out of a plane without knowing if the parachute would open.

As I took the plunge, I knew who would be with me—my best friend, the photographer Ed Feingersh, who knew all about parachuting. Some of his daring must have rubbed off on me, and we sat in Costello’s saloon planning our assault on Fortress Marilyn.

Three days later we had nothing. It dawned on me that while he was a daredevil, Eddie had no gifts as a stalker. The first afternoon he waited for hours in the lobby of Marilyn’s hotel, took a minute to make a phone call, and returned to find some kids waving the little Kodak Brownies that were the ubiquitous inexpensive camera of the day: “She posed for us!”

With blank pages looming in the July issue, I called Sam, a photographer who wanted to be a movie producer and had worked hard at friendships with Hollywood’s rising generation, among them Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando, and Marilyn. Sam and I had once shared an office, and he agreed to help.

At the Gladstone, Sam had called Marilyn on the house phone. As usual she was running late. We were nursing our drinks when a tall, tanned man looked into the room and headed for the table.

“Sam, how are you?” said Joe DiMaggio, sitting down. “Marilyn told me you were here.”

A few months earlier, avoiding reporters as usual, DiMaggio had been seen leaving divorce court in obvious sorrow and anger. Now here he was, fresh from his former wife’s room, talking, almost babbling about her with a schoolboy smile on his face, telling Sam how happy he was that she was away from “that movie crowd.” Moreover, the notoriously jealous DiMaggio was pressing him to see more of Marilyn. “She wants you to take her antiquing again,” he said, getting up to leave. He gave me a quick nod and smile.

A few minutes later Sam put me on the house phone, and in that familiar breathy voice, Marilyn agreed to do the picture story, suggesting we meet for a drink the next afternoon.

“Why,” Marilyn asked soon after we sat down, “do they print things about me that aren’t true?”

It was not a rhetorical question or a complaint. We were in a cocktail lounge, and she was looking at me over her Scotch Mist with a puzzled expression, waiting for an answer. Up close, her face was pale and fragile, with no Technicolor glow, and her eyes had none of the confidence that radiated from the screen.

Within minutes it was clear she had no small talk, no social defenses. Sam had told me, if you ask, “How are you?,” she will stop to think instead of coming back with an automatic “Fine.” And when she asked a question, she waited for an answer.

“Why do they make up stuff?” she persisted.

I took the plunge. “Because pictures of you sell papers and magazines, and when there’s no excuse for running them, they’ll print rumors and gossip, anything they can get.” Something pushed me to go further: “They don’t mean to hurt you, just use you.”

She looked at me with a flinching smile that said she knew all about being used. It set off a flash-back in my mind: Mike Cowles, the publisher of Look , telling of a visit to Twentieth Century–Fox in the late 1940s, when a studio head remarked, “We have a new girl on the lot with something unusual. Instead of sticking straight out, her tits tilt up.” He sent for Marilyn, who came in smiling, and he lifted her sweater to show what he meant. She never stopped smiling.

We talked about Sam for a while, and then Marilyn said, “There’s another reason I’m doing this: Your magazine never made fun of me.” Her eyes brightened. “Even gave me an award.”

I felt accepted and at the same time burdened with her trust. The most famously sexual woman in the world was being childlike and vulnerable but also using her openness to get what she wanted for a few days: my loyalty. All her life that mixture of innocence and guile had apparently drawn protectors and betrayers, many of them the same people.

It was not long before one popped up. The next day I got a call from Milton Greene, a mediocre photographer and world-class hustler who had persuaded her to form a partnership with him called Marilyn Monroe Productions. We can do the story, he said, but only with a photographer on his payroll. I told him to get lost, and when Eddie and I met Marilyn the next day, I related the shakedown attempt. She frowned, and we started on our story. (It took her a while to get the full picture, but eventually she fired Greene for mismanagement.)

I told Marilyn we wanted to show her as she really was: no poses, no blowing kisses to the camera, no studio setups, just a straight look at her life.

In the heyday of 35mm cameras and available light, Eddie worshiped Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose pictures were being shown not only in magazines but in museums. His idol would not allow prints to be cropped, and neither would Eddie. The “decisive moment” was framed in the photographer’s eye, and to change a picture later would be like taking slices off a Renoir or van Gogh. At a time when Italian and French films were showing up Hollywood fluff, Eddie and others were transforming traditional frozen magazine pictures with on-the-fly realism. The world was going grainy.

Alone among them, Eddie wanted to go beyond witnessing an event with the camera, to enter it and show how it looked from the inside—risking himself for moments nobody had ever seen. He took pictures while crawling with patrols in Korea, lashed to the periscope of a diving submarine, jumping from a plane with paratroops. Back home, on a racetrack with Irish Horan’s Lucky Hell Drivers, he crouched, elbows hugging his body, between boards tented at a 45-degree angle while speeding cars careened by so close he could see the ply marks on their tires.

Short, thin, and stooped, with a face far from handsome, Eddie was magnetic for everyone who knew him. He was as passionate about friendship as work. He was an artist at both.

He lived in the now, letting moments take him wherever they would. Costello’s was more home than hangout. He must have had an apartment or room somewhere, but in all our years as close friends, I never saw it. He got his mail and phone messages at Costello’s and spent every evening in town at the bar, as people he knew came and went, moving a few feet to a table for food and later, if the mood was right, slipping coins into the pay phone to ask some young woman to call her friends while a few of us brought over a bottle to drink and flirt away the night. His energy was unending. He would spend hours talking excitedly, gesturing, scrawling his version of Thurber dogs on napkins, getting up to pace around, crouched like Groucho in a serpentine glide. Life with him was never at a standstill.

Tracking Marilyn, Eddie’s camera was telling more than we knew at the time. The public Marilyn was keeping appointments—fittings for her costume to ride a pink elephant at a charity premiere of the circus, meetings with lawyers and agents (Twentieth Century–Fox had suspended her for decamping), a grand entrance in white furs at the opening night of Tennessee Williams’s new play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof . Before going out, she put on a performance with the stopper from a bottle of Chanel No. 5, stroking her skin in sensuous delight.

But between moments of being seen, there was another Marilyn, suddenly drained of energy, like the air being let out of a balloon. She sat in a darkening hotel room with drink in hand and went out on the terrace to stare unseeing at the Manhattan skyline. Eddie’s shutter kept clicking, and rolls of 35mm film filled up with images of the marilyn monroe you’ve never seen: withdrawn and alone. He never asked her to pose. She hardly knew he was there.

Marilyn had never been in a subway. Wrapped in the camel’s hair coat, her famous hair subdued, she walked to the Grand Central stop of the IRT and down to the platform. Nobody recognized her. Eddie’s camera kept clicking while she stood straphanging on the uptown local. No heads turned.

Back up on the street, Marilyn looked around with a teasing smile. “Do you want to see her ?” she asked, then took off the coat, fluffed up her hair, and arched her back in a pose. In an instant she was engulfed, and it took several shoving, scary minutes to rewrap her and push clear of the growing crowd.

The two Marilyns kept fading in and out. At the costume fitting she arrived as the Star, commanding a swarm of tailors, seamstresses, and hangers-on until the Other abruptly emerged and burst into tears of frustration over some detail of the garment. Eddie’s camera got it all, showing her rising tension against a visual jangle of wire hangers in the background. He framed the scene in the fragmented hall-of-mirrors unreality Orson Welles had created around Rita Hayworth for the finale of The Lady From Shanghai .

Late one afternoon Marilyn asked what we did at the end of the day, and we took her to Costello’s. By then John McNulty had been writing about the place in The New Yorker for years, but the proprietor, Tim Costello, managed to keep it from changing. A stern look over his teacup at the back table was more effective than the rules committee of any private club. Costello’s never went trendy in the way a cabdriver once said of another saloon, “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”

Behind the long bar was a blackthorn walking stick that had been broken over John O’Hara’s head by Ernest Hemingway, no one remembered why. On the facing wall were huge drawings on beaverboard by James Thurber, so valued by Tim that he had had them inked over, varnished, and, when he was forced to move his establishment next door, carefully removed and remounted. The panels were brown with age and tobacco smoke.

Thurber had filled the walls with images of cowardly canines (a dog being chased by rabbits) and little men menaced by huge women (“I’m leaving you, Myra, you might as well get used to the idea,” says one in the clutch of an Amazon several times his size). Such self-mocking masculinity suited the place. Tim did not abide noisy, pugnacious drunks.

Marilyn was wearing a black sleeveless blouse and striped slacks. She sat next to the Thurber drawings at a table across from the bar.

Tim, usually wary of strangers, was clearly intrigued by the blaze of blonde hair at our table and, in a rare gesture, came over to take the orders himself.

“A screwdriver please,” Marilyn said.

Tim was expressionless.

“Vodka and orange juice,” she added.

Tim kept looking at her. “We don’t serve breakfast here,” he said.

“O.K.,” Marilyn said agreeably, “vodka on the rocks.”

Tim gave the order to his brother Joe at the bar and went back to reading his paper. Later, as Eddie was heading to the men’s room, Tim stopped him.

“Who is she?”

Eddie smiled. “Marilyn Monroe.”

Tim’s face darkened. “I ask a civil question and you get smart.”

Eddie smiled again and Tim went back to his paper.

In the hour there no one else gave Marilyn more than a quick look. As she was leaving, a photographer at the bar tapped Eddie on the arm. “If you come back later,” he stage-whispered, “bring your little friend.”

The pictures in Redbook , with my text and captions, showed an unfamiliar, vulnerable Marilyn in soft shades of black and gray. The opening spread contrasted her solitary sadness with a long shot of 200 photographers almost trampling the elephant she was riding at the circus.

In their days together, despite the disparity in looks, I could see Eddie and Marilyn were much alike. They both were somehow more directly connected to life than the rest of us, and more vulnerable. Like Marilyn, Eddie was given to self-parody to mask the pain of being defenseless against daily living and, like her, desperate to make full use of the gifts such an open nature provides.

Just as Marilyn dreaded looking less than perfect in front of the cameras and was always late, so Eddie obsessed over what he did behind the camera and would let no one else develop or print his pictures.

Each held on to an ideal of Art as if it were life itself, and, as it turned out for both of them, it was. Marilyn’s movies and Eddie’s pictures made those who saw them feel more alive but at the same time fear for their safety, sensing the price that would have to be paid for their luminous openness.

Before the year was out, the Third Avenue el in front of Costello’s was torn down, removing the pillars Tim’s regulars would use to steady themselves while hailing cabs in the morning hours.

Marilyn’s stay in New York led to her marriage to Arthur Miller and an attempt to become a conventional wife and mother in Connecticut while making a few movies that showed acting ability as well as amplitude of flesh and spirit.

Eddie got married, too, and then he was in the crisis of his life.

The Cliff was a bar on Twenty-third Street. Eddie used his last dime for the phone call, and I went down to keep him from going over the edge.

It had started to go bad a couple of years after the Marilyn story. After my wedding we saw each other less, and so it came as a surprise when he told me he was getting married. She was a blank beauty with high cheekbones and an impervious air who drifted through our times together in a detachment that seemingly spurred Eddie to pour all the energy he used to put into finding the perfect picture into solving her mystery.

At their wedding I was behind the camera, looking at incongruous images of a picture-book bride in white alongside Eddie’s dark suit and sheepish smile, some part of him seeing it all in helpless bemusement. The marriage lasted a few months, during which he gradually worked less and less, then finally stopped altogether before his bride floated out of his life, leaving behind only her enigmatic stare.

After he called that evening, we sat for hours, trying to figure out what he could do, now that he was too paralyzed to do the one thing in life he was meant to do. Finally, I suggested an answer: “Come work for me. I need a picture editor.”

I was the editor of Redbook by then, and the idea made sense. If Eddie could no longer take pictures, he could imagine them, match photographers to subjects, and help them do good work until he could start doing his own again.

For a few months it went well. Once in a while, when he was excited about an assignment, I would say without looking at him, “Of course, you’d be perfect for it,” or, “It’s your kind of story.” Each time he would freeze for a moment before his eyes went blank and he shook his head.

He cut down on his drinking, but the depression got worse. Gradually he came into the office less and less and finally not at all. Then came a phone call from a woman who had been in love with him for years. He had arrived at her door the evening before and died in his sleep during the night.

Over the years I had urged Eddie to try a psychiatrist, but my pleading could not break through his certainty that suffering was inseparable from his gift, that he could not escape one without losing the other. In today’s world he—and Marilyn, for that matter —might have been kept going by medication, but back then there was no such lifeline.

Ever since, those who loved Eddie’s work have tried to get museums to give him the recognition he deserves. But it has been no easier to help him in death than it was during his life. Almost all his prints and negatives, so closely held, scattered and disappeared, magnificent pictures lost forever.

Yet something of him remains alive, linked forever with that other lost soul. On Web sites, in many languages, people are selling prints of a few of those pictures Eddie took of Marilyn that week in 1955. The negatives were found in a warehouse three decades after his death.

Marilyn has inspired rescue fantasies in legions of writers, among them Norman Mailer and Gloria Steinem. Toward the end of his life Arthur Miller looked back and saw himself that way. “I spent five years trying to keep her from falling off the cliff,” he told an interviewer in 2004 while justifying After the Fall , the nasty piece of self-pity he wrote soon after her death.

As Eddie’s would-be savior, I am left with no such soothing consolation, only an abiding sense of loss.

A Marilyn Monroe Chronology.

/image%2F1211268%2F20240315%2Fob_782fd3_banner-mm-2024-03-spring-5.jpg)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240410%2Fob_40c4f9_blog-gif-mm-niagara-1-3.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240417%2Fob_0b0d56_2024-03-lee-mexique.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F65%2F312561%2F91436129_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F63%2F312561%2F127743382_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F05%2F312561%2F84823731_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F63%2F312561%2F84814201_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F21%2F312561%2F82823948_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F32%2F31%2F312561%2F124125043_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F31%2F08%2F312561%2F71448014_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F90%2F312561%2F81829009_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F18%2F35%2F312561%2F61120383_o.jpg)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240410%2Fob_9f471d_blog-gif-mm-syi-1.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240229%2Fob_66f2c6_tag-mm-public-martin-lewis-show-1.png)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240410%2Fob_07cb4a_blog-gif-mm-stern-1.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240229%2Fob_143453_blog-gif-video.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240301%2Fob_735dec_blog-liens-culture.jpg)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240302%2Fob_e11252_blog-liens-friends-jane.gif)