Photography

country: USA

published in June 1953

content: 8 pages article on Marilyn Monroe

The Marilyn session photos by Philippe Halsman for Life April, 7, 1952

is here explained by the photographer himself

pays: USA

paru en juin 1953

contenu: article de 8 pages sur Marilyn Monroe

La séance de Marilyn par Philippe Halsman pour Life 7 avril 1952

est ici détaillée par le photographe lui-même

- summary: "Shooting Marilyn... Philippe Halsman" - p66

- Pages : article "Shooting Marilyn"

Article: Shooting Marilyn

by Philippe Halsman

WHEN A PHOTOGRAPHER is asked by a photographic magazine for a set of pictures he is unhappy if he cannot offer a selection of his best and most unusual photographs. Thus I was unhappy when PHOTOGRAPHY asked me for my story on Marilyn Monroe which was only a rather typical Life assignment. But realizing that the most noble purpose of a photographic magazine is educational, and that there is not presently in Hollywood a more educationnal subject than Marilyn, I agreed sadly but willingly.

Actually, I had photographed her a couple of years before I shot my cover story. At that time she was a very intense and hard-working at putting the best points of her anatomy in the public eye. Her blouses and sweaters made it easy to guess what they were supposed to hide.

I was working then on a Life story about Hollywood starlets. To find out how good the were (as actresses) the editor, Gene Cook, invited eight of them and I photographed each one in four basic situations: listening to the funniest but inaudible joke, enjoying the most delicious but invisible drink, being frightened by the most horrible invisible monster, and finally, being kissed by the most fabulous invisible lover.

If Marilyn was a standout among the eight starlets, it was not for her acting ability in the first three of the tests. But when I asked her to act out the last basic situation, I changed my mind. She gave a performance of such realism and such dramatic intensity that not only she but even I was utterly exhausted.

I met Marilyn again three years later. She was not yet a star, but already all the aging women in Hollywood hated her. I was struck by the change. She no longer tried to be sexy - she was sexy in the most unabashed and relaxed way.

There was already a flattering legend of dumbness about her, for Hollywood likes to surround its beautiful blondes with the bewitching aura of imbecility. What indeed could add more to the attractiveness of an enchantress than the complete absence of brains ? Unfortunately the facts did not confirm the legend. I found Marilyn anything but stupid, with an amazing frankness and a good sense of humor, and her company stimulating even in a spiritual way. The trait which struck me most was a general benevolence, an absolute absence of envy and jealousy, which in an actress was astonishing.

By coincidence, a week after this meeting, Life's reporter Stanley Flink informed me that his magazine wanted me to shoot Monroe for a possible cover, with a few supporting pictures to be used inside -probably two pages. We got in touch with the studio and were told that Marilyn would be available for a day and a half. I specified that I didn't want to shoot her in the studio, and a meeting in her hotel was arranged.

Now I had to decide what kind of photographs I would make. Some photographers shoot only by instinct, and though they often get beautiful individual pictures, they have difficulty in putting together a cohesive picture story. Others follow closely a shooting script and force their material into such conformity that it loses spontaneity and sincerity. In my photography I try to avoid the pitfalls of either category. Of course I don't avoid shooting by instinct whan an interisting situation offers itself to me. On the other hand, I consciously try to use my intellect as much as possible. I strive to clarify my own thinking about the subject and to organize the picture material in terms of story conitunuity and layout, being careful however not to make my subjects pose, but to incite them to do things they are used to doing.

First I had to find a theme for my story, a general idea to carry through all my pictures. I thought how I had tried to capture the essence of other women: Ingrid Bergman's radiant wholesomeness; Anna Magnani - a tragic tigress; Cecile Aubry - half child, hald woman, tempting and disturbing; Marian Anderson, singing Negro spirituals, full of priestly dignity.

And then I thought of the pathetic struggle of a poor starlet in Hollywood. Among the crowd of beautiful girls who never made the grade, Marilyn was not the one who had the most beautiful face or the most elegant figure. So why was she successfull ? Because sha was a good actress ? Nobody had yet mentionned her acting ability. But even if the great Duse were alive, would any Hollywood studio make an effort to hire her ? I doubt it. CBut I am sure that if Italy had an actress who surpassed Jane Russell and Dagmar in their most conspicuous attributes, every movie company would come running to outbid the others.

Who were the great movie stars ? Theda Bara, the "It" Girl Clara Bow, Pola Negri, Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich. A few of them could even act, but in the last analysis their fabulous "glamour" was nothing but their special brand of sex appeal

And in the case of Marilyn Monroe I saw the amazing phenomenom of Hollywood being outsmarted by a girl whom it had itself characterised as a dumb blonde.

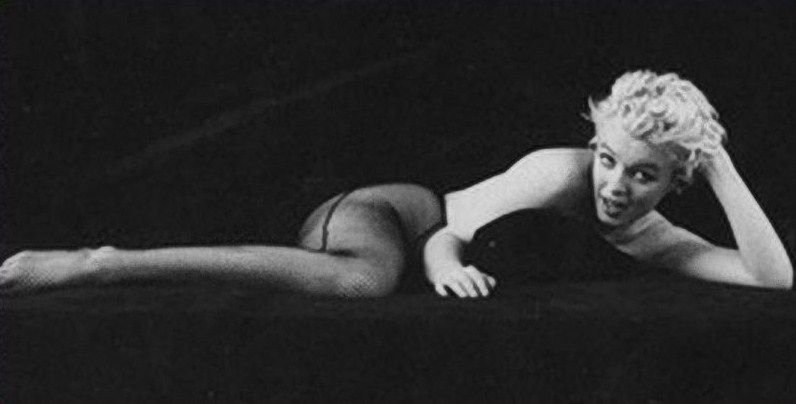

As usual, analysis led logically and almost inescapably to the theme of the story. I had to show in my pictures that Monroe's sexiness was not only her weapon but her very essence, that it permeated everything she did - talking, walking, sitting, eating, lying down. In terms of a layout everything became equally clear and simple. I had to produce and opening picture, establishing the general theme. The rest of the story would be photographs showing Marilyn in different situations, proving my point.

On the appointed day we arrived on time in front of Monroe's hotel: Life's Stanley Flink, my assistant John Baird and I. Marilyn was of course late. Finally she drove up in her not-exactly-new Pontiac convertible, apologized for being late, and we all went up to her room. It was medium-sized, with a big couch-like bed, with gymnastic aquipment on the floor and with a lot of bookshelves along the wall. Marilyn wore blue jeans and looked as unaffected as the proverbial girl next door. The was immediately a feeling of palship and of having fun. "What do you do with these dumbbells ?" I asked when I almost tripped over a couple of them. "But Philippe, I am fighting gravity !" Marilyn answered gravely, and inhaled deeply to prove her point.

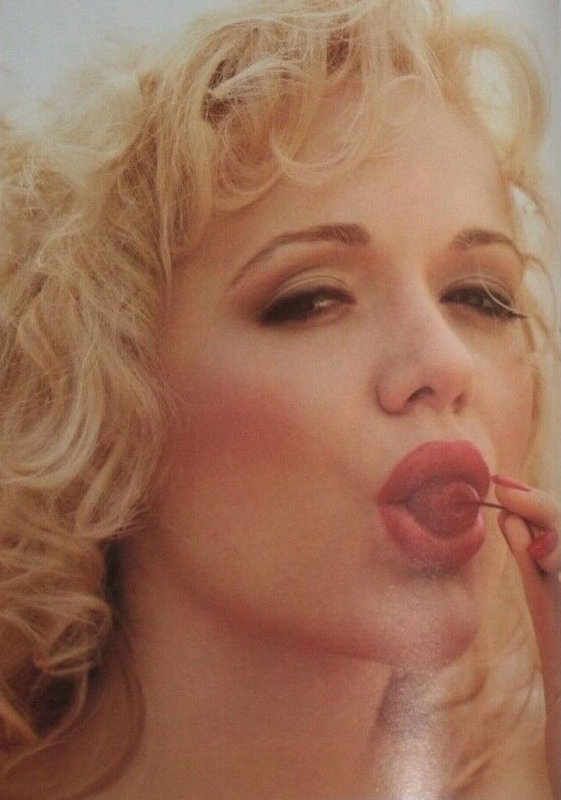

I decided to begin by trying for a cover picture. First I had to find the dress. Marilyn opened her closet and I found to my surprised that one of the reasons why Monroe wore so little was that she had so little to wear. She obviously was spending more money on books and records than on dresses. There were no furs in her wardrobe and only a couple of evening gowns. I selected the white slinky one, and Marilyn put it on. It had an enormous bow on the left hip. I explained to Marilyn that the bow cheapened the gown, that as a rule simple lines in a dress were more elegant. Marilyn, after listening to me with the attention of a pupil listening to a teacher's explanation of a new algebra theorem, took her scissors and cut off the bow.

While she was in the bathroom overhauling her makeup (I insisted that she not to wear more than lipstick and mascara), I was thinking of the way she should pose. The obvious would have been to shoot her reclining in an armchair or on her couch, but because it was so obvious I decided against it. I led Marilyn to a corner and put my camera in front of her. Now she looked as if she had been pushed into the corner - cornered - with no way to escape. The basic situation was provided, and I had only two remaining worries: the lighting, and Stanley Flink.

I use my Fairchild-Halsman camera almost exclusively for photographing faces. It would have been wasteful to concentrate on Monroe's face, since she uses her body (for acting) more than any other Hollywood actress. Consequently I decided to shoot her with a Rolleiflex, and an aperture of f/5.6 seemed to me appropriate. At that stop my Weston meter indicated, in spite of the big window behind me, only 1/3 second. My assistant brought from the car thow #2 floodlamps in aluminium reflectors and I put one on a portable stand in front of Marilyn. Now, using the big window as a fill-in and the flood as the main light, i could shoot at 1/10 or 1/25 second, depending on the distance. My assistant attached the second light to the top of an adjacent closet so that it illuminated and backlighted Marilyn's blond hair. The lighting problem solved, there remained the question of Stanley Flink.

Reporters frequently insist on watching the actual shooting session. The mere fact of being observed usually inhibits both model and photographer, creating an atmosphere of self-consciousness which destroys the necessary intimacy between cameraman and subject. But fortunately for me in this case, nature has blessed Flink with a charming and helpful disposition. He is never the cold, impartial observer; he immediatly and enthusiastically becomes a part of the working team.

He placed himself near the camera ans started to compliment and to tease Monroe. I pretended to be very jealous of him and we had a fiery verbal battle, both unabashedly competing for Marilyn's favor. Surronded by three admiring men, she smiled, flirted, giggled, and wriggled with delight. During the hour I kept her cornered she enjoyed herself royally, and I... I took between 40 and 50 pictures - not of the stock expressions she usually gives to the photographers.

Why did I take so many pictures, instead of being satisfied with four or five ? I shoot when the expression seems significant, but I never know whether the next moment might not produce and even more rewarding expression. Nothing seems cheaper to a magazine photographer then unexposed film. The great number of exposures makes the subject disregard the importance of being photographed, and creates sometimes a complete immunization against the constant clicking of the shutter. I stop shooting when I feel that the situation has reached its climax. I was extremely happy to see later that the Life editors had selected as the cover the picture made at that climactic instant.

My next step was to review Marilyn's negligees. The Twentieth Century-Fox publicity man, Roy Craft, who is in charge of Marilyn, but is nevertheless particularly efficient and cooperative, had sent over ten different negligees. I selected the one I thought would photograph the best and started to look for a background. My curiosity was aroused by the only photograph in the room. To my surprise I recognized the face of Eleonora Duse. Did Marilyn display this picture just to impress itinerant intellectuals ? I asked a few questions and was startled to find that Marilyn not only knew a lot about her, but that the Divine Duse was her great idol.

An old rule of mine, when making a reportage, is to photograph everything which is significant or startling. This was both. I decided to include Duse's photograph in my opening picture. There was a record player on the bookshelf. Marilyn, in a transparent negligee, leaned against it, listening with breathless dreaminess to a record. Her derrière was pointing toward Duse's immortal face. To me it was no sacrilege. It was my ironic comment on the shift of values in our civilization.

Marilyn's bookshelves were full of the most disparate books -about religion, science, history, psychology, and translations of French, Russian, and German classics. That too was startling, and a good opportunity to make and educational picture. My next photograph showed the gorgeous blonde, in her transparent negligee, sitting with a book in her lap, wistfully working on her intellectual development. It was truly inspirationnal. Behind Marilyn's figure, eggheads could study the titles of her books. This was the last picture of the first day.

The next day, on our way to lunch, I took the opportunity of photographing Marilyn's remarkable walk, trying to catch its amazing turbinoid undulation. I made any exposures, for I had the feeling that, rhythmically, at the peak of its lilting tortility, it winked at me, but that I constantly missed catching the wink. With a movie camera it would have been child's play, but to seize the essence of the walk in one shot, if it was possible at all, demanded the utmost apperceptive concentration.

After lunch, we drove to a drive-in restaurant to show that Marilyn looks sexy even while eating. After this, I made the series of pictures showing Monroe's technique in applying for a job which were used in Life. Then we took the speedlights to her room, and with indirect lighting I photographed her exercising with dumbbells, crawling on the floor, standing on her head, and doing pushups and handstands. I thought this would be the last set of pictures. We packed our equipment and carried it down the stairs. Looking up, I saw Marilyn leaning over the railing to see us off. It looked like a well-composed photograph. I called "hold it !" and opened my Rollei to take another two dozen shots of her there.

The assignment had been typical in every respect, and when I returned to New York I was not surprised to find that as usual the magazine story did not resemble the layout the photographer originally had in mind. Life put Marilyn on the cover and made a very unexpected but journalistically shrewd move: in the opening page of the story they used the nude now-famous calendar shot of the nude Monroe. This single picture was undoubtedly more newsworthy than my entire coverage. To use my picture of her in a transparent negligee next to it would have been anticlimactic. So, since I was in New York, another photographer was asked to shoot her in sweater and slacks. The next page consisted of six shots from my set of Marilyn's approach to a job. The last page showed her magnificent walk, next to a similar photograph of Jean Harlow, also taken from behind.

For Marilyn this was probably the most important magazine story in her carrer. I have seen Life covers which did nothing for their protagonists, and I have also seen cases in which they literally changed a life or skyrocketed an unknown to fame. Although in Marilyn's case the effect was not of spectacular immediacy, this story did convince Twentieth Century-Fox that instead of a mere starlet with possibnilities, they had in her a star of the first magnitude. Monroe got star billing even in movies where she played secondary parts; her salary was adjusted, she moved to better quarters, and she is now doubtless the hottest actress in Hollywood.

For me it was only a routine story which resulted in my 54th Life cover (currently I have 60), and being routine, it is a good example of my day-by-day work. Some of my friends say that like Columbus who, trying to find the way to the Indies, discovered for the world a new continent. I, attempting to capture Monroe's personnality, discovered for the American public her derrière. It is true that since my Life story her entire publicity has rotated around this axis, and Monroe's walk was one of the main features of her latest movie.

Traduction Photographier Marilyn

par Philippe Halsman

QUAND UN PHOTOGRAPHE est sollicité par un magazine de photos pour un reportage photos, il est mécontent s'il ne peut pas offrir une sélection de ses meilleures et de ses plus rares photos. Ainsi, j'étais mécontent quand PHOTOGRAPHY m'a sollicité pour mon histoire sur Marilyn Monroe qui n'était qu'une sorte de sujet de Life assez typique. Mais réalisant que le but le plus noble d'un magazine photographique est éducatif, et qu'il n'y a actuellement à Hollywood pas de sujet plus éducatif que Marilyn, j'ai accepté tristement mais volontiers.

En fait, je l'avais photographiée quelques années avant de faire ma couverture avec elle. À cette époque, elle travaillait très intensément et durement pour mettre les meilleurs atouts de son anatomie aux yeux du public. Ses chemisiers et ses pulls permettaient de deviner facilement ce qu'ils étaient censés cacher.

Je travaillais alors pour Life pour une histoire sur les starlettes d'Hollywood. Pour découvrir à quel point elles étaient bonnes (en tant qu'actrices), l'éditeur, Gene Cook, en a invité huit et j'ai photographié chacune d'entre elles dans quatre situations de base : écouter la blague la plus drôle mais inaudible, savourer la boisson la plus délicieuse mais invisible, avoir peur du plus horrible des monstres invisible, et enfin, être embrassé par le plus fabuleux des amants invisible.

Si Marilyn s'est distinguée parmi les huit starlettes, ce n'était pas pour son talent d'actrice dans les trois premiers des tests. Mais quand je lui ai demandé de mimer la dernière situation de base, j'ai changé d'avis. Elle a donné une performance d'un tel réalisme et d'une telle intensité dramatique que non seulement elle mais même moi étions complètement épuisés.

J'ai rencontré à nouveau Marilyn trois ans plus tard. Elle n'était pas encore une star, mais déjà toutes les femmes vieillissantes d'Hollywood la détestaient. J'ai été frappé par le changement. Elle n'essayait plus d'être sexy - elle était sexy de la manière la plus éhontée et la plus détendue.

Il y avait déjà chez elle une légende flatteuse du mutisme, car Hollywood aime entourer ses belles blondes de l'aura envoûtante de l'imbécillité. Qu'est-ce en effet qui pourrait ajouter plus à l'attrait d'une enchanteresse que l'absence totale de cervelle ? Malheureusement, les faits n'ont pas confirmé la légende. J'ai trouvé Marilyn tout sauf stupide, avec une franchise étonnante et un bon sens de l'humour, et sa compagnie stimulante, même d'un point de vue spirituel. Le trait qui me frappait le plus était une bienveillance générale, une absence absolue d'envie et de jalousie, ce qui chez une comédienne étonnait.

Par coïncidence, une semaine après cette rencontre, le journaliste de Life, Stanley Flink, m'a informé que son magazine voulait que je photographie Monroe pour une éventuelle couverture, avec quelques photos à l'appui à utiliser à l'intérieur - probablement deux pages. Nous avons contacté le studio et on nous a dit que Marilyn serait disponible pour un jour et demi. J'ai précisé que je ne voulais pas la filmer en studio, et un rendez-vous à son hôtel a été organisé.

Maintenant, je devais décider quel genre de photographies je voudrais faire. Certains photographes ne photographient que par instinct, et bien qu'ils obtiennent souvent de belles photos individuelles, ils ont du mal à mettre en place une histoire d'images cohérente. D'autres suivent de près une séance scénarisée et forcent leur matériel à une telle conformité que cela perd de la spontanéité et de la sincérité. Dans ma photographie, j'essaie d'éviter les pièges de l'une ou l'autre catégorie. Bien sûr, je n'évite pas de filmer par instinct lorsqu'une situation intéressante s'offre à moi. D'un autre côté, j'essaie consciemment d'utiliser mon intellect autant que possible. Je m'efforce de clarifier ma propre réflexion sur le sujet et d'organiser le matériel de l'image en termes de continuité et de mise en page de l'histoire, en prenant garde cependant à ne pas faire poser mes sujets, mais à les inciter à faire ce qu'ils ont l'habitude de faire.

J'ai d'abord dû trouver un thème pour mon histoire, une idée générale pour mener à bien toutes mes images. J'ai pensé à la façon dont j'avais essayé de capturer l'essence d'autres femmes : la santé radieuse d'Ingrid Bergman ; Anna Magnani - une tigresse tragique; Cécile Aubry - moitié enfant, moitié femme, tentante et dérangeante ; Marian Anderson, chantant de la musique noire spirituelle, pleine de dignité sacerdotale.

Et puis j'ai pensé à la lutte pathétique d'une pauvre starlette à Hollywood. Parmi la foule de belles filles qui n'ont jamais eu de diplôme, Marilyn n'était pas celle qui avait le plus beau visage ou la silhouette la plus élégante. Alors pourquoi a-t-elle réussi ? Parce que c'était une bonne actrice ? Personne n'avait encore évoqué son talent d'actrice. Mais même si la grande Duse était vivante, un studio hollywoodien ferait-il un effort pour l'embaucher ? J'en doute. Mais je suis sûr que si l'Italie avait une actrice qui surpassait Jane Russell et Dagmar dans leurs attributs les plus remarquables, chaque société de cinéma accourrait pour surenchérir sur les autres.

Qui étaient les grandes stars de cinéma ? Theda Bara, la "It" Girl Clara Bow, Pola Negri, Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich. Quelques-unes d'entre elles pouvaient même jouer, mais en dernière analyse, leur fabuleux "glamour" n'était rien d'autre que leur sex-appeal spécial. Et dans le cas de Marilyn Monroe, j'ai vu l'incroyable phénomène d'Hollywood se faire déjouer par une fille qui elle-même était qualifiée de blonde stupide.

Comme d'habitude, l'analyse a conduit logiquement et presque inéluctablement au thème de l'histoire. Je devais montrer dans mes photos que la sensualité de Monroe n'était pas seulement son arme mais son essence même, qu'elle imprégnait tout ce qu'elle faisait - parler, marcher, s'asseoir, manger, s'allonger. En termes de mise en page, tout est devenu également clair et simple. J'ai dû produire une image d'ouverture, établissant le thème général. Le reste de l'histoire serait constitué de photographies montrant Marilyn dans différentes situations, prouvant mon point de vue.

Le jour du rendez-vous, nous sommes arrivés à l'heure devant l'hôtel de Monroe : Stanley Flink de Life, mon assistant John Baird et moi. Marilyn était bien sûr en retard. Finalement, elle est arrivée dans son cabriolet Pontiac pas tout à fait neuf, s'est excusée d'être en retard et nous sommes tous montés dans sa chambre. C'était de taille moyenne, avec un grand lit ressemblant à un canapé, avec du matériel de gymnastique sur le sol et avec de nombreuses étagères le long du mur. Marilyn portait un blue jean et semblait aussi indifférente que la voisine proverbiale d'à côté. Ce fut tout de suite un sentiment de complicité et de plaisir. "Que faites-vous avec ces haltères ?" J'ai demandé quand j'ai failli trébucher sur quelques-unes d'entre elles. "Mais Philippe, je combats la gravité !" Marilyn répondit gravement et inspira profondément pour prouver son point de vue.

J'ai décidé de commencer par essayer la photo de couverture. Je devais d'abord trouver la robe. Marilyn a ouvert son placard et j'ai découvert à ma grande surprise que l'une des raisons pour lesquelles Monroe était si peu vêtue était qu'elle avait si peu à porter. Elle dépensait manifestement plus d'argent en livres et disques qu'en robes. Il n'y avait pas de fourrures dans sa garde-robe et seulement quelques robes de soirée. J'ai choisi la robe moulant blanche, et Marilyn l'a mise. Il y avait un énorme arc sur la hanche gauche. J'expliquai à Marilyn que le nœud dépréciait la robe, qu'en règle générale les lignes simples d'une robe étaient plus élégantes. Marilyn, après m'avoir écouté avec la même attention qu'un élève écoutant l'explication de son professeur sur un nouveau théorème algébrique, prit ses ciseaux et coupa l'arc.

Alors qu'elle était dans la salle de bain en train de refaire son maquillage (j'insistais pour qu'elle ne porte pas plus que du rouge à lèvres et du mascara), je réfléchissais à la façon dont elle devrait poser. L'évidence aurait été de la photographier allongée dans un fauteuil ou sur son canapé, mais parce que c'était tellement évident, j'ai décidé de ne pas le faire. J'ai emmené Marilyn dans un coin et j'ai mis mon appareil photo devant elle. Maintenant, elle avait l'air d'avoir été poussée dans un coin - acculée - sans aucun moyen de s'échapper. La situation de base était prévue, et il ne me restait plus que deux soucis : l'éclairage, et Stanley Flink.

J'utilise mon appareil photo Fairchild-Halsman presque exclusivement pour photographier des visages. Il aurait été inutile de se concentrer sur le visage de Monroe, car elle utilise son corps (pour jouer) plus que toute autre actrice hollywoodienne. J'ai donc décidé de la photographier avec un Rolleiflex, et une ouverture de f/5,6 m'a semblé appropriée. A cet arrêt mon compteur Weston indiquait, malgré la grande vitre derrière moi, seulement 1/3 de seconde. Mon assistant a apporté de la voiture des projecteurs #2 dans des réflecteurs en aluminium et j'en ai mis un sur un support portable devant Marilyn. Maintenant, en utilisant la grande fenêtre comme remplissage et le projecteur comme lumière principale, je pouvais photographier à 1/10 ou 1/25 seconde, selon la distance. Mon assistant a fixé la deuxième lumière en haut d'un placard adjacent afin qu'elle éclaire et rétro-éclaire les cheveux blonds de Marilyn. Le problème d'éclairage résolu, il restait la question de Stanley Flink.

Les journalistes insistent souvent pour regarder la séance photos proprement dite. Le simple fait d'être observé inhibe généralement à la fois le modèle et le photographe, créant une atmosphère de conscience de soi qui détruit l'intimité nécessaire entre le caméraman et le sujet. Mais heureusement pour moi dans ce cas, la nature a béni Flink avec une disposition charmante et serviable. Il n'est jamais l'observateur froid et impartial ; il devient immédiatement et avec enthousiasme un membre de l'équipe de travail.

Il s'est placé près de l'appareil et a commencé à complimenter et à taquiner Monroe. J'ai fait semblant d'être très jaloux de lui et nous avons eu une bataille verbale enflammée, tous deux se disputant sans vergogne les faveurs de Marilyn. Entourée de trois hommes admiratifs, elle souriait, flirtait, gloussait et se tortillait de plaisir. Pendant l'heure où je l'ai gardée coincée, elle s'est amusée royalement, et j'ai... j'ai pris entre 40 et 50 photos - pas les expressions courantes qu'elle donne habituellement aux photographes.

Pourquoi ai-je pris autant de photos, au lieu de me contenter que de quatre ou cinq ? Je photographie lorsque l'expression semble significative, mais je ne sais jamais si le moment suivant ne produira pas une expression encore plus gratifiante. Rien ne semble moins cher à un photographe de magazine qu'un film non exposé. Le grand nombre d'expositions fait que le sujet néglige l'importance d'être photographié, et crée parfois une immunisation complète contre le cliquetis constant de l'obturateur. J'arrête de photographier quand je sens que la situation a atteint son paroxysme. J'ai été extrêmement heureux de voir plus tard que les éditeurs de Life avaient choisi comme couverture la photo prise à cet instant décisif.

Ma prochaine étape consistait à passer en revue les déshabillés de Marilyn. Le publicitaire de la Twentieth Century-Fox, Roy Craft, qui dirige Marilyn, mais est néanmoins particulièrement efficace et coopératif, avait envoyé plus de dix déshabillés différents. J'ai sélectionné celui qui, selon moi, serait le mieux rendu en photo et j'ai commencé à chercher un arrière-plan. Ma curiosité a été éveillée par la seule photographie dans la pièce. À ma grande surprise, j'ai reconnu le visage d'Eleonora Duse. Marilyn a-t-elle affiché cette image juste pour impressionner les intellectuels itinérants ? J'ai posé quelques questions et j'ai été surpris de découvrir que Marilyn en savait non seulement beaucoup sur elle, mais que la Divine Duse était sa grande idole.

Une vieille règle à moi, quand je fais un reportage, est de photographier tout ce qui est significatif ou surprenant. C'était les deux. J'ai décidé d'inclure la photo de Duse dans ma photo d'ouverture. Il y avait un tourne-disque sur l'étagère. Marilyn, en déshabillé transparent, s'y adossa, écoutant avec une rêverie haletante un disque. Son derrière pointait vers le visage immortel de la Duse. Pour moi, ce n'était pas un sacrilège. C'était mon commentaire ironique sur le changement de valeurs dans notre civilisation.

Les étagères de Marilyn étaient pleines des livres les plus disparates - sur la religion, la science, l'histoire, la psychologie et les traductions de classiques français, russes et allemands. Cela aussi était surprenant et une bonne occasion de faire une image éducative. Ma photo suivante montrait la magnifique blonde, dans son déshabillé transparent, assise avec un livre sur ses genoux, travaillant avec nostalgie sur son développement intellectuel. C'était vraiment inspirant. Derrière la silhouette de Marilyn, des têtes d'œufs pouvaient étudier les titres de ses livres. C'était la dernière photo du premier jour.

Le lendemain, sur notre chemin pour aller déjeuner, j'en ai profité pour photographier la marche remarquable de Marilyn, essayant de saisir son étonnante ondulation turbinoïde. Je faisais toutes les expositions, car j'avais l'impression que, rythmiquement, au sommet de sa tortilité chantante, comme me faisant un clin d'œil, mais que je manquais constamment d'attraper ce clin d'œil. Avec une caméra, cela aurait été un jeu d'enfant, mais saisir l'essence de la démarche d'un seul coup, si cela était possible, exigeait la plus grande concentration perceptive

Après le déjeuner, nous sommes allés dans un restaurant drive-in pour montrer que Marilyn était sexy même en mangeant. Après cela, j'ai fait la série de photos montrant la technique de Monroe pour postuler à un emploi qui ont été utilisées dans Life. Nous avons emmené les flashes dans sa chambre, et avec un éclairage indirect, je l'ai photographiée en train de faire de l'exercice avec des haltères, rampant sur le sol, se tenant sur la tête et faisant des pompes et des poiriers. Je pensais que ce serait la dernière série de photos. Nous avons remballé notre équipement et l'avons transporté dans les escaliers. Levant les yeux, j'ai vu Marilyn se pencher par-dessus la balustrade pour nous voir partir. Cela ressemblait à une photographie bien composée. J'ai interpellé: "Attends !" et j'ai ouvert mon Rollei pour prendre encore deux douzaines de photos d'elle là.

Le reportage avait été typique à tous les égards, et quand je suis retourné à New York, je n'ai pas été surpris de constater que, comme d'habitude, le reportage du magazine ne ressemblait pas à la mise en page que le photographe avait initialement en tête. Life a mis Marilyn en couverture et a fait un geste très inattendu mais astucieux sur le plan journalistique : dans la première page du reportage, ils ont utilisé la photo du désormais célèbre calendrier de Monroe nue. Cette image unique était sans aucun doute plus digne d'intérêt que toute ma couverture. Utiliser ma photo d'elle dans un déshabillé transparent à côté aurait été décevant. Alors, comme j'étais à New York, on a demandé à un autre photographe de la photographier en pull et pantalon. La page suivante se composait de six plans de mon ensemble de l'approche de Marilyn à un travail. La dernière page montrait sa magnifique marche, à côté d'une photographie similaire de Jean Harlow, également prise de dos.

Pour Marilyn, ce fut probablement l'histoire de magazine la plus importante de sa carrière. J'ai vu des couvertures de Life qui n'ont rien fait pour leurs protagonistes, et j'ai aussi vu des cas dans lesquels ils ont littéralement changé une vie ou fait monter en flèche un inconnu à la gloire. Bien que dans le cas de Marilyn, l'effet n'ait pas été d'une immédiateté spectaculaire, cette histoire a convaincu la Twentieth Century-Fox qu'au lieu d'une simple starlette avec des possibilités, ils avaient en elle une étoile de première grandeur. Monroe a obtenu la vedette même dans les films où elle a joué des rôles secondaires; son salaire a été ajusté, elle a déménagé dans de meilleurs quartiers et elle est maintenant sans aucun doute l'actrice la plus sexy d'Hollywood.

Pour moi, ce n'était qu'une histoire de routine qui a abouti à ma 54ème couverture de Life (actuellement j'en ai 60), et en tant que routine, c'est un bon exemple de mon travail au jour le jour. Certains de mes amis disent cela comme Colomb qui, essayant de trouver le chemin des Indes, découvrit pour le monde un nouveau continent. Moi, en essayant de saisir la personnalité de Monroe, j'ai découvert pour le public américain son derrière. Il est vrai que depuis mon histoire dans Life, toute sa publicité tourne autour de cet axe, et la marche de Monroe était l'une des principales caractéristiques de son dernier film.

© All images are copyright and protected by their respective owners, assignees or others.

/image%2F1211268%2F20240315%2Fob_782fd3_banner-mm-2024-03-spring-5.jpg)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240410%2Fob_40c4f9_blog-gif-mm-niagara-1-3.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240417%2Fob_0b0d56_2024-03-lee-mexique.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F65%2F312561%2F91436129_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F63%2F312561%2F127743382_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F05%2F312561%2F84823731_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F63%2F312561%2F84814201_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F21%2F312561%2F82823948_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F32%2F31%2F312561%2F124125043_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F31%2F08%2F312561%2F71448014_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F90%2F312561%2F81829009_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F18%2F35%2F312561%2F61120383_o.jpg)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240410%2Fob_9f471d_blog-gif-mm-syi-1.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240229%2Fob_66f2c6_tag-mm-public-martin-lewis-show-1.png)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240410%2Fob_07cb4a_blog-gif-mm-stern-1.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240229%2Fob_143453_blog-gif-video.gif)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240301%2Fob_735dec_blog-liens-culture.jpg)

/image%2F1211268%2F20240302%2Fob_e11252_blog-liens-friends-jane.gif)